Parallel Planning with MoveIt 2

MoveIt 2 has a new planning interface that enables the use of multiple motion planning algorithms in parallel to solve a planning problem. From all produced solutions, the best one is chosen based on a user-defined solution selection callback. With this interface, the planning algorithm selection is simplified and it is possible to use fallback planners in case a preferred planner occasionally fails. This blog post introduces the new feature in detail and the newly added parallel planning tutorial explains how it can be used.

Motivation

Robotic motion planning is hard: One of the biggest challenges is the careful selection of a planning algorithm to find a path in a high-dimensional space that satisfies a set of constraints. A good planning algorithm should be fast, compute high-quality paths, and abort planning within a reasonable time if no solution exists. MoveIt 2 currently supports multiple planning libraries: OMPL, CHOMP, STOMP, and PILZ. Each of these libraries has strengths and weaknesses as summarized in Table 1.

| OMPL |

|

|

| PILZ |

|

|

| CHOMP & STOMP |

|

|

Table 1: Comparison of available MoveIt 2 planner plugin libraries

Choosing the most suitable library for a specific planning problem is challenging. Often, a motion planning stack does not only have to solve a single problem type but a broad variety of problems, ranging from free space motions to navigating through a cluttered environment. None of the planning libraries is a jack of all trades. How do you choose the best planning algorithm for a group of diverse and possibly unknown planning problems? To address this question, we developed a new interface for moveit_cpp to enable using multiple planning algorithms in parallel. It allows for defining a stopping criterion for choosing the best result from all generated solutions. Users don’t have to select the right algorithm for a planning problem anymore, they can simply let them all run and compete with each other. All that is needed is a stopping criterion (1) that captures the right balance between planner speed and optimality and a selection criterion (2) that defines what is considered the best solution.

Implementation

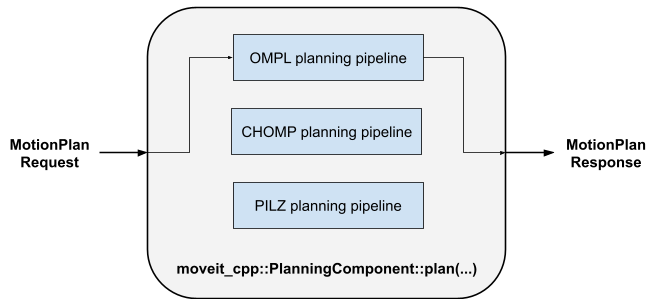

The parallel planning interface for MoveIt 2 is an enhancement of the existing moveit_cpp interface. The currently used single-pipeline interface can be seen in Figure 1. The MotionPlanRequest contains a definition of the planning problem and the selected planning pipeline. The planning pipeline computes a motion plan response that contains the solution.

Figure 1: Default moveit_cpp single pipeline setup

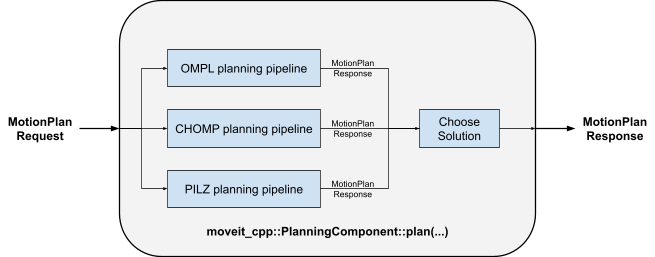

The new parallel planning interface is built around the existing architecture. Figure 2 shows its operation flow.

Figure 2: Parallel planning moveit_cpp setup

Instead of selecting an individual planning pipeline, a selected set of planning pipelines is used. The planning problem is solved independently multiple times in different parallel planning pipelines. All created MotionPlanResponses are collected in a thread-safe data storage. Once a stopping criterion is met, the existing MotionPlanResponses are forwarded to a solution selection function which then chooses the best solution. The solution selection function can be either defined by the user or a default implementation can be used. Which solution is considered the best highly depends on the planning problem. Possible quality criteria are for example planning time, execution time, path length, clearance from collision objects, or trajectory smoothness.

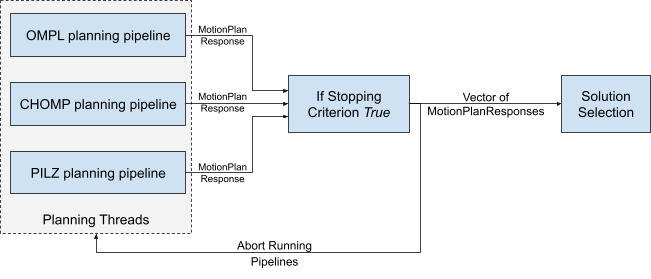

In addition to a customizable solution selection function, the new interface offers the option to define a stopping criterion for the parallel running pipelines. If the available solutions are likely to contain the best solution before all pipelines are finished, there is no point in waiting for the remaining planners. Figure 3 visualizes the additional infrastructure that enables aborting planning pipelines once a stopping criterion is met.

Figure 3: Stopping Criterion

Aborting all other planning pipelines as soon as one pipeline finds a solution, to optimize for planning speed, would be an example of a heuristic for a stopping criterion.

Furthermore, the stopping criterion function has access to the produced solutions, which can be useful to decide whether a “good enough” solution has been found. Some planners produce optimal solutions, while others focus more on feasibility. So if an optimal solution is found, planning can be aborted immediately, but if a feasible solution is found, a user may want to wait for a better solution from another planner (up to some time limit).

With this framework, it is easier to apply MoveIt 2 in scenarios where it is hard to choose the best single planning pipeline. Instead of choosing the most suitable planning pipeline, a definition of the best solution can be provided and the best solution from a set of planning pipelines can be chosen automatically.

Benchmarks

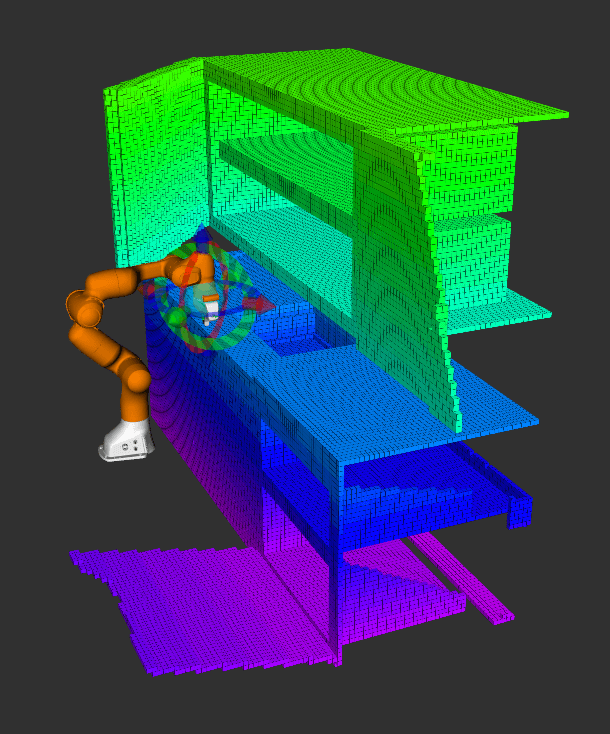

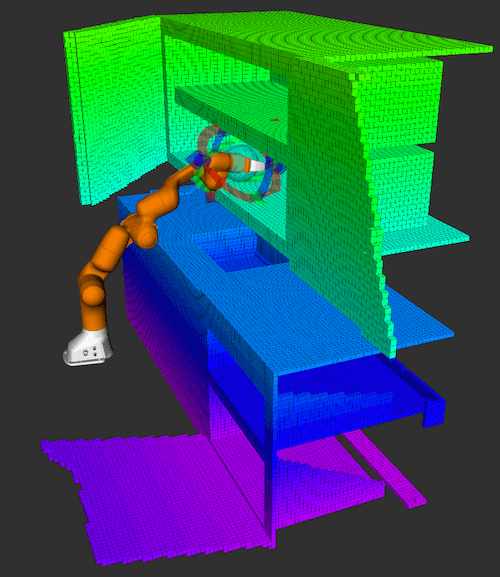

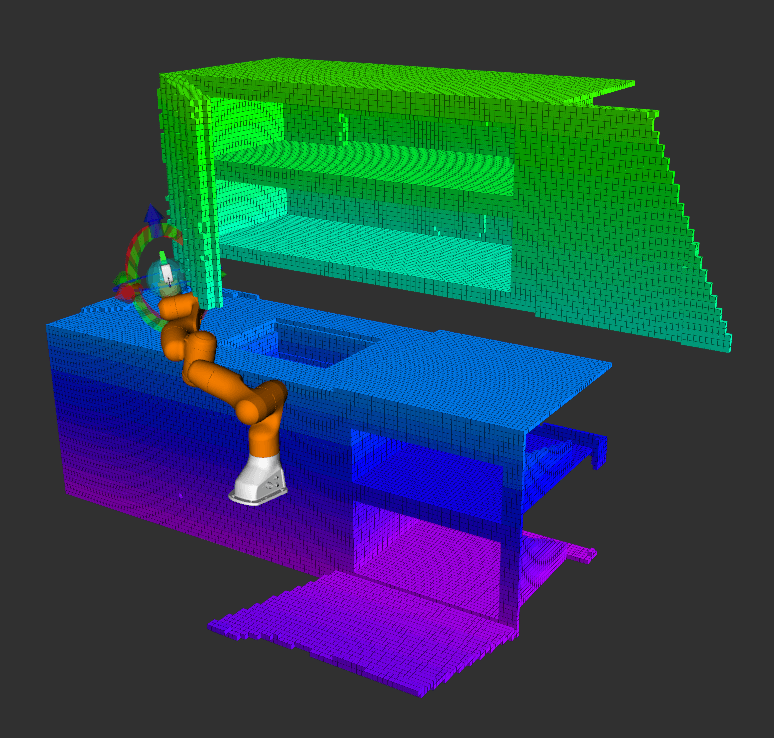

Let’s take a closer look at the scenarios in which the parallel planning interface provides an advantage. To benchmark the parallel planning pipelines against a single pipeline setup, a robot arm is driven to different locations in a kitchen environment to simulate real-world pick-and-place tasks. The setup and the start configuration of the robot can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Kitchen environment and start configuration

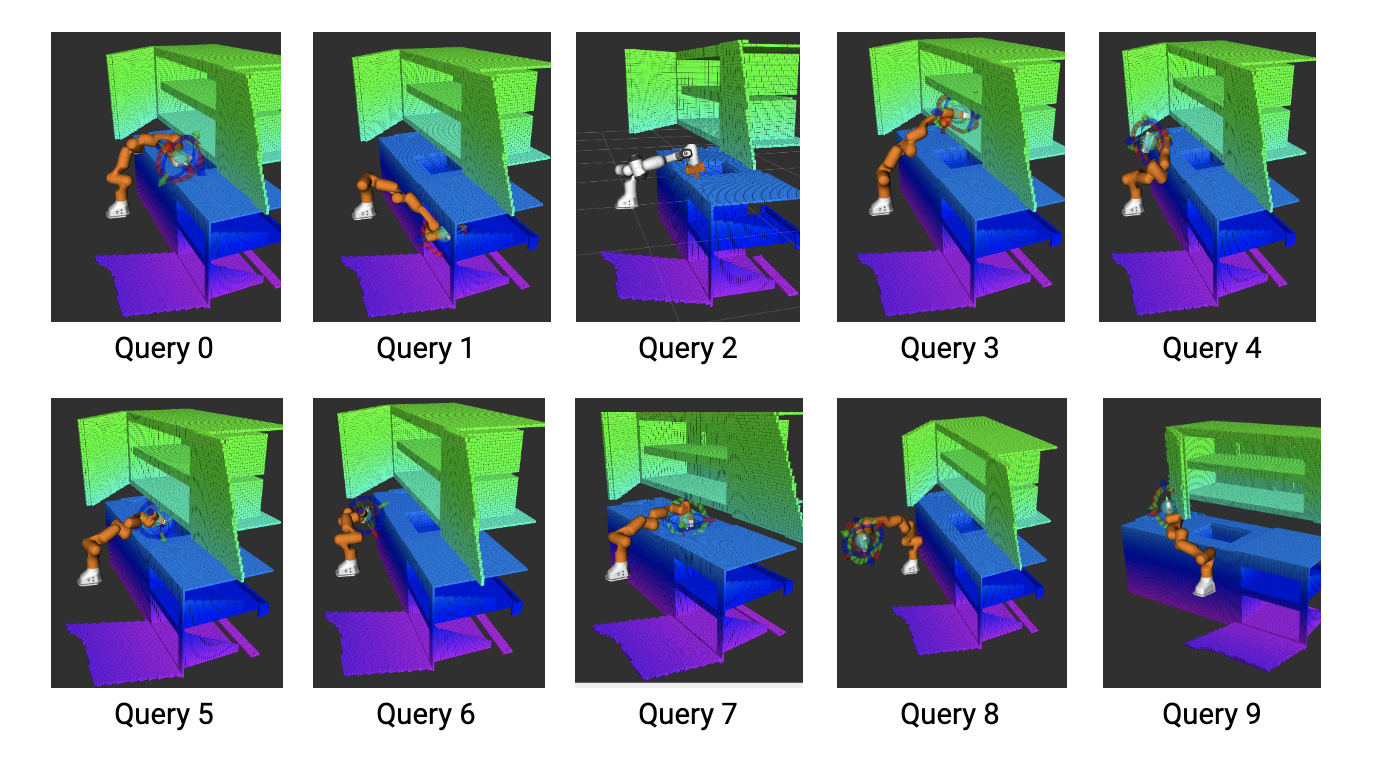

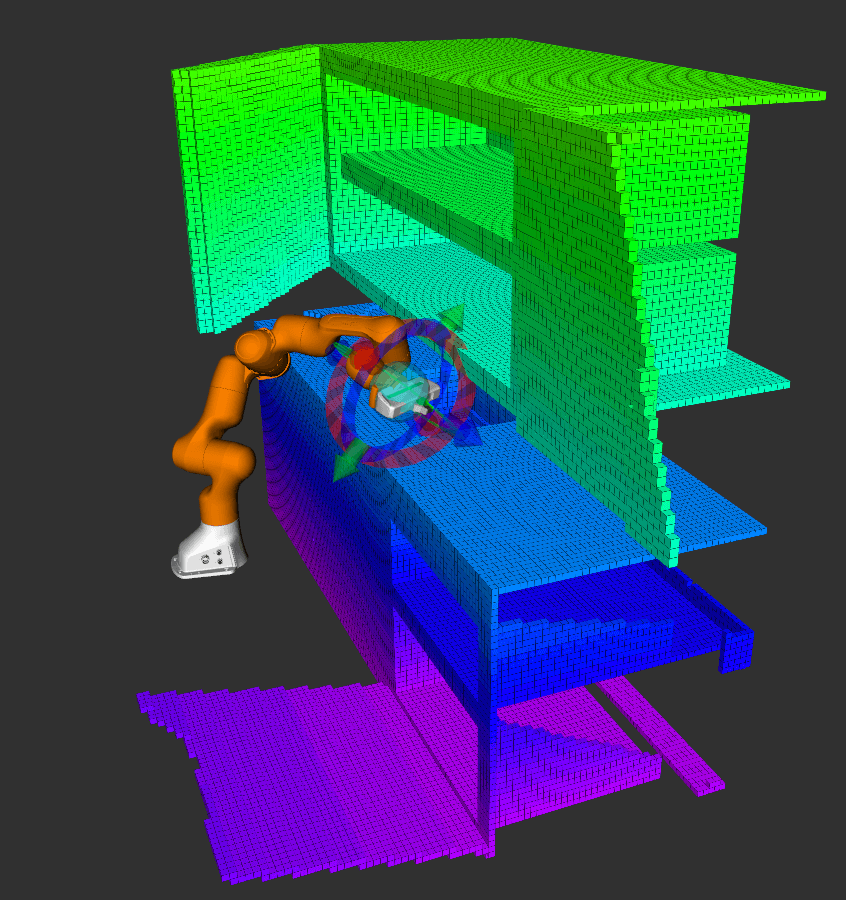

10 different planning problems (queries) are solved. A variety of “easier” and “harder” poses is chosen as goal poses which can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Queries

For each query, the problem is solved 50 times with a 1.5-second time limit. The solution with the shortest path is considered the best solution. Hence, the following discussion of the results will be around the path length. CHOMP, OMPL, and PILZ are chosen as single planning pipelines. The parallel planner uses all three pipelines with the same configuration in parallel and chooses the solution with the shortest path. Table 2 contains a summary of the benchmark configuration.

| Number of Queries | Iterations per Query | Max. Planning Time | Best solution | Planner (Planning Pipeline) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 50 | 1.5s | Shortest Path(L1 norm in Joint Space) |

|

Table 2: Benchmark configuration

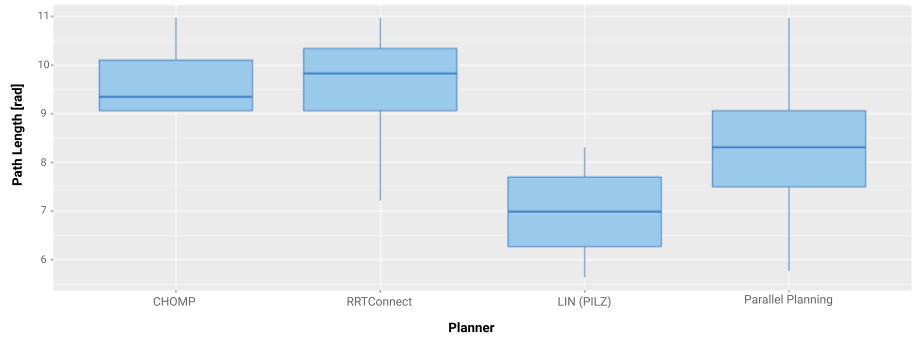

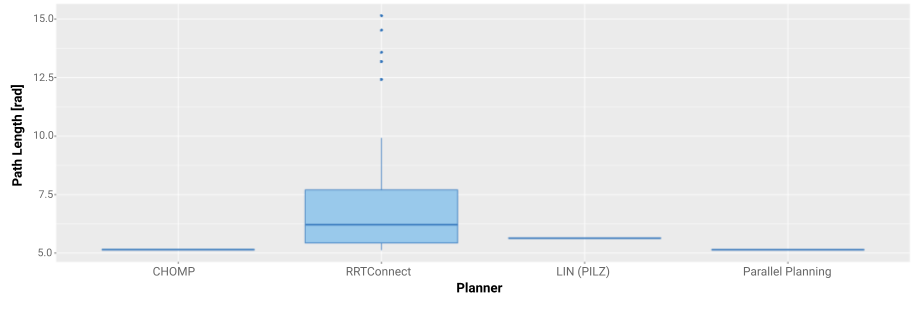

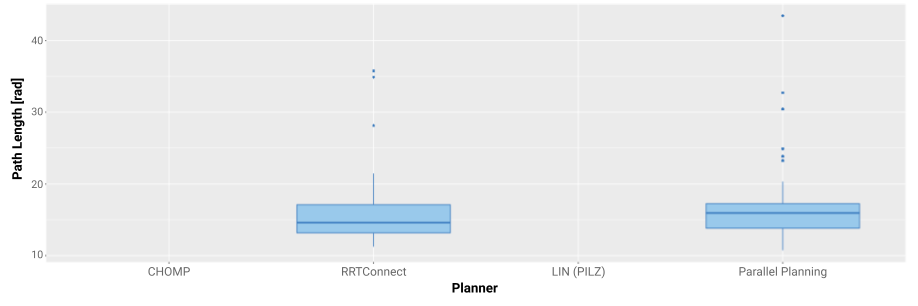

Looking at the average results of all queries, the parallel planning interface outperforms the single planners in terms of path length. In each planning query, the solution of the planner that produced the shortest path is chosen, so it is no surprise that the parallel planner produces the best results over a broad range of motion planning problems with different difficulties as seen in Figure 6. At first glance, PILZ seems to outperform the parallel planner, but it is only able to solve 40% of the planning problems. Hence, the parallel planning interface produces the shortest paths on average over all queries.

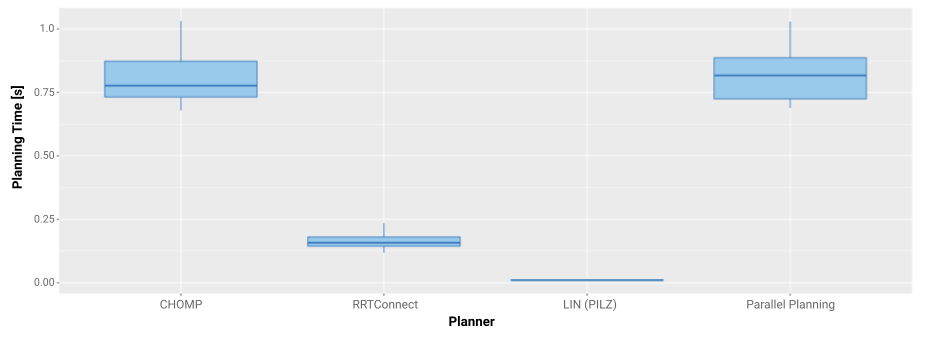

But higher path quality is not always for free. Looking at the planning times in Figure 7, the parallel planner takes as long as the longest-running individual planner: CHOMP. If more information about the use case is available, it is possible to improve the behavior by choosing a good stopping criterion. A stopping criterion does not have to be a very sophisticated complex algorithm. In many cases, simple heuristics can provide a huge improvement for example stopping the parallel planning if the pipeline, which produces most likely the best solution, is successful.

| Planner | Percentage Solved from 500 Queries |

|---|---|

| CHOMP | 67% |

| LIN | 40% |

| OMPL | 100% |

| Parallel Planning | 100% |

Figure 6: Path lengths and success rates of all queries

Figure 7: Planning times of all queries

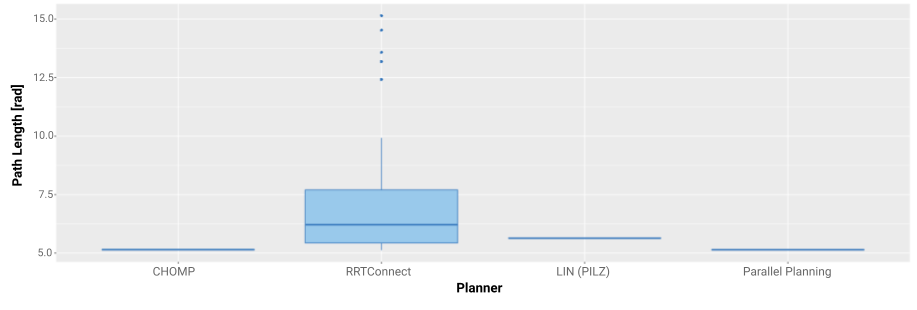

Let’s take a look at some individual queries to see the impact of parallel planning on a specific planning problem. The first example is Query 3 seen in Figure 8. All planners manage to solve the planning problem but CHOMP always provides the shortest path and the parallel planner performs as well as CHOMP.

| Planner | Solved |

|---|---|

| CHOMP | 50/50 |

| LIN | 50/50 |

| OMPL | 50/50 |

| Parallel Planning | 50/50 |

Figure 8: Path lengths and success rates of Query 3

CHOMP is always able to converge against the same and shortest solution within the available planning time. RRTConnect does not provide a deterministic solution and thus produces paths with different lengths for each query. LIN performs a Cartesian interpolation which is the same solution every time, but not the shortest path in joint space. Using parallel planning helps to choose the best planning pipeline since it might not have been intuitive that CHOMP is always the best choice here.

In the second example, shown in Figure 9, the planning problem is not solved by all planners every time. PILZ is never able to solve the planning problem, and although CHOMP creates the shortest path, it occasionally fails.

| Planner | Solved |

|---|---|

| CHOMP | 80% |

| LIN | 0% |

| OMPL | 100% |

| Parallel Planning | 100% |

Figure 9: Path lengths and success rates of Query 7

The box plot of the parallel planner shows the occasional selection of the RRTConnect results, which appear as outliers in the otherwise very deterministic boxplot. Here, parallel planning enables a fallback solution if the usually most suitable planner fails.

Query 9 is a very hard motion planning problem: from the start state a path around a collision object needs to be planned with the end joint configuration very close to a collision object.

| Planner | Solved |

|---|---|

| CHOMP | 0% |

| LIN | 0% |

| OMPL | 100% |

| Parallel Planning | 100% |

Figure 9: Path lengths and success rates of Query 9

As seen in Figure 10, only RRTConnect is able to solve this motion planning problem and thus, parallel planning does not bring any advantage over single pipeline planning. Slight differences between the two box plots can be explained by the non-determinism of RRTConnect. The more benchmark iterations are done, the more will the two boxplots match. If it is clear that a motion planning architecture is used for a specific family of problems where a single planner clearly outperforms all other planners, that planner should be used.

Conclusion

No motion planner excels in solving all possible planning problems. Choosing a single motion planner is always a trade-off between path quality, planning time, and completeness. Parallel planning circumnavigates the disadvantages of a single planner by using multiple planners at the same time and choosing the best one based on the results created. Nevertheless, it is not always the best choice.

Use parallel planning

- to find the best solutions in a broad variety of problems

- when it is unclear which planner will produce the best solution for a given problem

- if your best planner choice can fail, and you need a fallback planner

Don’t use parallel planning

- when you want to solve motion planning problems where it is already clear that one planner excels

- where you want to explicitly rely on specific planner traits, like roadmaps or cost functions that are not supported by alternatives

- if you have limited computation resources

When you use parallel planning, keep in mind that you need to customize the stopping criterion and solution selection. Only a configuration tailored to the specific problem will provide the most optimal results. If you’re interested in using MoveIt’s parallel planning interface, get started by reading the tutorial. Don’t hesitate to share your configuration for feedback or contribute a custom solution selection or stopping criterion to MoveIt 2!